Fostering = The Lessons of Letting Go

When I told my teenage son a foster puppy was coming to our house that evening, he rolled his eyes.

“Why us?” he asked, his voice whiney, as if it really was us who would be doing the work, “why should we do all the work? So annoying.” He turned back to his computer and Facebook.

By the next day, said son had posted numerous pictures of the uber-cute foster puppy on his FB page.

“You know what?” He sounded incredulous. “I get more ‘likes’ from these puppy pictures than any of my other Facebook posts.”

“Still annoyed?” I asked. He smiled but didn’t answer.

I fostered quite a few dogs in the past, before my partner and I took in two foster kids, whom we then adopted, this son and one other. Our plate was full enough for several years, no need to add any foster dogs. But the boys are older now and our own dogs – pitbull mixes as it happens – are flexible and friendly. We have room for one more dog at a time without coming apart at the seams.

Our first foray back into foster care was last year. At the time we had two dogs. Now we have three. Do the math; you can see how that foster situation worked out. This go-round, we are committed to being a successful foster family, which means we will let the dog – no matter how cute, cuddly, and loveable – move on to another family for adoption.

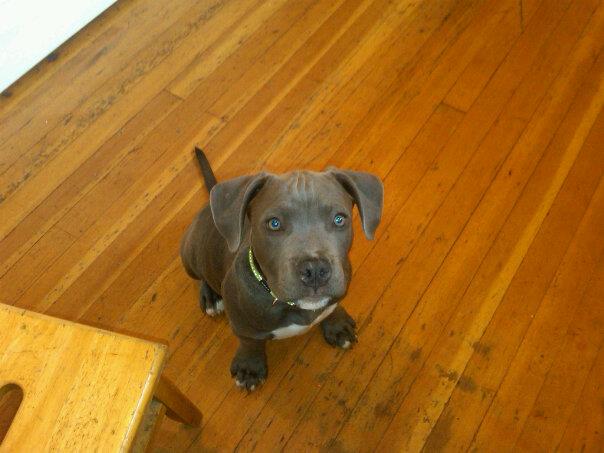

The first case tested our foster-only metal. Fourteen weeks old, the gray-and-white male pitbull puppy was the very definition of loveable. In the first five minutes, my eleven-year old son piped up with the predictable, “Can we keep him?”

“No.” I was emphatic.

Being an adorable puppy ensured that this little guy would have lots of interested adopters. The organization who rescued him – Born Again Pitbull Rescue – scrutinized applications and found a wonderful home for the young punk within less than a week of his arrival at our house. When someone came to pick up our foster puppy and take him to his adopters, my young son was not happy.

“What if he’s afraid? What if he can’t sleep through the night?” At the puppy’s departure he cried, worried for the dog’s safety and happiness.

“Maybe we shouldn’t do this again,” I broached with him later. Maybe, I thought, the process was just too hard for a kid who was former foster himself; maybe it triggered too many memories and feelings of loss and fear. “If we do, we have to let them go.”

“Why?” He wailed and put his head down on his folded hands.

I shook my head. I wanted to keep on fostering, but this isn’t just about me. “I think we’re not ready yet. We can wait a while before we have another one.”

“No.” He sat straight up. “I can do it.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.” He nodded. “It saves lives.”

That it does.

Fostering allows shelters to care for puppies too young to be adopted, to provide animals who need medical care or training the opportunity to get what they need, or to save animals who just need to be pulled out of an overcrowded shelter before they get put down.

If you’ve never fostered a puppy or a dog, contact the Oregon Humane Society, Family Dogs New Life Shelter, or the county animal control shelters and apply to become a foster provider. Breed rescue organizations need foster families too, so you might foster a pitbull, a pug, a retriever, or almost any other breed you love.

I won’t lie; it’s extra effort. But after all, as my son knows, it saves lives.